The good news is that both locations, Gadsden’s Wharf in South Carolina and Valongo Wharf in Rio de Janeiro, stand on the verge of recognition, restoration, and memorialization but at far distant stages. Individually and together, they represent attempts to honor the victims of the largest forced migration in human history. But grief will not reign supreme at either location. They will be places of vibrant celebration of African history and culture as well.

The International African American Museum in Charleston, at the Gadsden Wharf site, will begin its timeline in 300 BC, linking West African rice cultivation and the human history of that part of the continent. The formal history of the museum begins with the "discovery" of the remains of the wharf as part of property that was originally sold to a restaurateur. The former mayor, Joseph P. Riley, approved a re-acquisition of the parcel, having a sense of the timeliness and importance of such a project to the city's Black residents and its prospects to further spur tourism (and perhaps unknowingly gentrification).

Two decades ago, as a journalist recently recollected, Charleston was a "sleepy Navy town juxtaposed within an old aristocratic porch society." Riley had bigger plans.

The museum's planning began more than two decades ago.

Today, the city is a target for millions of tourists, cruise ship passengers, and a new breed of snowbirds now realizing that they don't need to fly all the way to Florida for higher temperatures. Actual construction began in January 2020. The opening was set for January 21, 2023, but recently postponed.

A trove of African artifacts were unearthed at the Valongo level, including amulets and worship objects from the Congo, Angola, and Mozambique.

Meanwhile, Charleston's perennial racial problems were on display for the world to see: battles over confederate flags and statues, the Mother Emmanuel shooting, and the city's formal apology for its role in the slave trade.

Riley was able to corral $100 million dollars in funding for museum construction from the city, state, other localities, and organizations. In 2018, The New York Times had recognized that Charleston had long needed and deserved a Black museum.

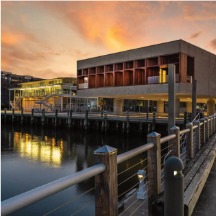

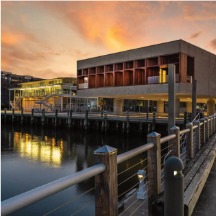

The structure, on top of the wharf, will have a sweeping view of the river and recurring architectural motifs of granite and water. There will be a theater gallery, ethnobotanical gardens, an African roots and routes gallery, and much more. In a membership solicitation letter, current president and CEO Dr. Tonya Matthews states, ".... And today something new has sprung up through the scarred soil of Gadsden's Wharf. We have reclaimed this sacred place as only part of the African American journey by building the museum on this very ground." Many in the city are holding their collective breathes waiting for opening day; the unspoken dream of generations of Black Charlestonians who had always hoped that their lives and struggles would not be consigned to oblivion.

In an article entitled "Valongo: An Uncomfortable Legacy,” Current Anthropology magazine (Vol. 61, No. S22) noted that: "In 2011, the United Nations promoted the International Year for People of African Descent in order to 'redouble our efforts to fight against racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia, and related intolerance that affect people of African descent everywhere.'" That same year, in a happy coincidence, Valongo Wharf was unearthed in Rio de Janeiro, the largest port of arrival for enslaved Africans in Brazil in the nineteenth century. Archeological excavations had been made possible by the urban infrastructure works carried out in the port area for the 2016 Olympics."

From Gadsden's Wharf, USA to Valongo Wharf, Brazil - Memory and Healing - Part 4 of 4

Praising the Past

Two wharfs were actually "discovered," Valongo and Imperatriz, one on top of the other with Imperatriz the uppermost structure as if to conceal what happened at Valongo. A trove of African artifacts were unearthed at the Valongo level, including amulets and worship objects from the Congo, Angola, and Mozambique. The Brazilian National, Historic, and Artistic Heritage Institute and the city of Rio applied for and soon received a UN designation for Valongo as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Or "discoverers" could have simply followed the trail of bones. Human remains had been found by local workers for years near the wharf in the vicinity of the Cemetery of the New Blacks; a final resting place for "...bodies, which were often covered in open sores and underfed"... and were put to final rest.

The use of such a term as "discovered" also seems to miss the mark since the area around the wharf is called "Little Africa" and dates to the time of the actual slave trade. And considering that Brazil did not end slavery until 1888, the last nation in the western hemisphere to do so, it is likely that some local Afro-descendants still have quite vivid recollections of Valongo handed down by their no too distant ancestors.

Concerned local residents did mounte a campaign to preserve the area and form an institute. Chronic underfunding by the city nearly led to the institute closing in 2017.

The racially conscious portion of the Rio's Black community was also deeply stirred by news of the excavations. They "appropriated" the site conducting religious and cultural ceremonies, including, for example, periodic "washings of the wharf" to cleanse it of the spiritual suffering and the pain endured there. Exponents of the Afro-Brazilian martial arts known as capoeira have gathered there making cultural presentations. Additional research at the site has generated a novel, a documentary, local tourism., and the promulgation of a charter calling for the erection of a diaspora memorial.

Now that Valongo has captured international attention, a large number of stakeholders--some old, some new-- have emerged just in time to comment on the current mayor's plan to create a slavery and freedom museum in Rio's larger port zone. In addition to arguments over location, finances, racism, resources, and potential corruption, there is growing alarm over the creeping gentrification in the area.

Whatever happens a uniquely Brazilian solution will triumph. As Sarah Zewde, an Ethiopian American urban planner with much experience in the city, has observed: "...Rio possesses both the demand for an African museum and the people and the energy necessary to make it an institution on the cutting edge of commemorations of the African diaspora worldwide."

Someone once noted that: "the life of the dead is placed in the memory of the living." It is inspiring to see that people of goodwill in both far flung locations are united in such a sacred endeavor.

Part 1 - From Gadsden's Wharf, USA to Valongo Wharf, Brazil

Part 2 - From Gadsden's Wharf, USA to Valongo Wharf, Brazil – The Fall of Charleston and The Rise of Freedom

Part 3 - Blood on The Palm Trees

Or "discoverers" could have simply followed the trail of bones. Human remains had been found by local workers for years near the wharf in the vicinity of the Cemetery of the New Blacks; a final resting place for "...bodies, which were often covered in open sores and underfed"... and were put to final rest.

The use of such a term as "discovered" also seems to miss the mark since the area around the wharf is called "Little Africa" and dates to the time of the actual slave trade. And considering that Brazil did not end slavery until 1888, the last nation in the western hemisphere to do so, it is likely that some local Afro-descendants still have quite vivid recollections of Valongo handed down by their no too distant ancestors.

Concerned local residents did mounte a campaign to preserve the area and form an institute. Chronic underfunding by the city nearly led to the institute closing in 2017.

The racially conscious portion of the Rio's Black community was also deeply stirred by news of the excavations. They "appropriated" the site conducting religious and cultural ceremonies, including, for example, periodic "washings of the wharf" to cleanse it of the spiritual suffering and the pain endured there. Exponents of the Afro-Brazilian martial arts known as capoeira have gathered there making cultural presentations. Additional research at the site has generated a novel, a documentary, local tourism., and the promulgation of a charter calling for the erection of a diaspora memorial.

Now that Valongo has captured international attention, a large number of stakeholders--some old, some new-- have emerged just in time to comment on the current mayor's plan to create a slavery and freedom museum in Rio's larger port zone. In addition to arguments over location, finances, racism, resources, and potential corruption, there is growing alarm over the creeping gentrification in the area.

Whatever happens a uniquely Brazilian solution will triumph. As Sarah Zewde, an Ethiopian American urban planner with much experience in the city, has observed: "...Rio possesses both the demand for an African museum and the people and the energy necessary to make it an institution on the cutting edge of commemorations of the African diaspora worldwide."

Someone once noted that: "the life of the dead is placed in the memory of the living." It is inspiring to see that people of goodwill in both far flung locations are united in such a sacred endeavor.

Part 1 - From Gadsden's Wharf, USA to Valongo Wharf, Brazil

Part 2 - From Gadsden's Wharf, USA to Valongo Wharf, Brazil – The Fall of Charleston and The Rise of Freedom

Part 3 - Blood on The Palm Trees

Advertisers | Contact Us | Events | Links | Media Kit | Our Company | Payments Pier

Press Room | Print Cover Stories Archives | Electronic Issues and Talk Radio Archives | Writer's Guidelines