Much has been written and much has been said about the great abolitionists from the eastern seaboard. This includes the accounts of slavery objectors from Frederick Douglass of Washington to Williams Lloyd Garrison of Boston and freedom seekers such as Harriet Tubman of Dorchester County, Maryland.

But look at who had the means to control the narrative. Around 1840, when the Underground Railroad was in full swing, Boston, with about 95,000 citizens, was home of the elite and many of those who documented and disseminated history. Shikaakwa, the Native American word for Chicago, on the other hand, was a small town, about the size of its current Loop (downtown), with only about 5,000 people.

The story of freedom seeker Caroline Quarlls and her escape should be told along with that of Harriet Tubman, especially to Midwestern children.

Since around 1999, under various names, The Little Calumet River Underground Railroad Project of Chicago has been balancing this old east coast narrative. The volunteer group researches resistance stories from the great Midwest and memorializes them in a variety of ways including via a recent Underground Railroad tour in a rural/industrial area at Chicago's southern edge.

As our tour group stood on the Indiana Avenue Bridge that spans the Calumet-Saganashkee (Calumet-Sag) Channel/Little Calumet River, Professor Larry McClellan, explained “Between roughly 1820 and 1861, about one-third of the 4,500 freedom seekers who traveled through Chicago crossed the river at this point, then called the Riverdale Crossing ferry and bridge."

Spookily, as a commuter train crossed the river on the nearby Illinois Central Railroad tracks, he added that scores later other Blacks would more freely leave the South for Chicago over those same tracks during the Great Black Migration (1916-1970). (Those migrants included my parents.)

Interestingly, many of those passengers on the commuter train are probably descendent of the migrators and were heading home to one of Chicago’s majority Black south suburban villages.

In the 1800s, many of the formerly enslaved Africans who crossed the river were helped by Dutch immigrant farmers including the Ton family. McClellan, a long-time civil rights advocate, went on to point out that part of the nearby Ton family farm now includes a marina owned by a former Chicago policeman, or one of Chicago’s “finest,” Ron Grimes. Grimes, who is of African descent, calls the former safe house and riverfront grounds Chicago’s “Finest” Marina.

In addition to memorializing the ground’s history with a historic marker, the site will soon include picnic grounds, pontoons, and kayaking. With the group’s advocacy, The National Park Service now includes the farm/marina on its National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom registry.

As the tour bus carried us to former small farm plots once cared for by Blacks who had arrived during The Great Black Migration, McClellan reminded us that the land once served as safe territory for freedom seekers.

The former professor at Governors State University in South Suburban Chicago admits that the history of the land was probably never shared with the small plot farmers, but added that the story of freedom seeker Caroline Quarlls and her escape should be told along with that of Harriet Tubman, especially to Midwestern children.

“This was activity in our own backyard,” exclaimed the co-author of “To the River: The Remarkable Journey of Caroline Quarlls, a Freedom Seeker on the Underground Railroad.” He wrote the book with one of her direct descendants Kimberly Simmons.

Underground Railroad – This Stop: Metro Shikaakwa (Chicago)

Praising the Past

Quarlls is the first known enslaved person to escape from Wisconsin. She like thousands who would follow her used the safes houses similar to the Tons on their route to freedom. (See Freedom Seeker Caroline Quarlls (Walker))

Eerily, McClellan and I amusingly noted that many now associate the Dutch with the anti-Blackness of apartheid in South Africa and Germans with anti-Black Naziism.

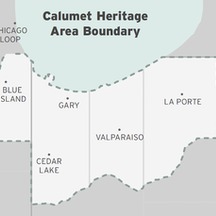

Then 16-year-old Quarlls started her journey in St. Louis, where she was enslaved. She escaped in 1842, headed north to Milwaukee, south to Chicago, and around Lake Michigan via what would become Gary before arriving in Detroit to cross the Detroit River into Canada and freedom.

The road she traveled from Chicago to Detroit, the Detroit to Chicago Road, was built in 1824 after the U.S. government negotiated a right of way with the Native communities. When building the road, the Americans generally followed trails Native Americans had used for centuries. Present-day Interstate 94 generally parallels the Detroit-Chicago Road and the ancient trails.

Similar to the Ton family, who were Dutch immigrants, many of the early station managers who helped Quarlls were newly arrived Germans. Eerily, McClellan and I amusingly noted that many now associate the Dutch with the anti-Blackness of apartheid in South Africa and Germans with anti-Black Naziism.

On the opposite site of the former safe house is a closed Chicago dump. Even to get to the former safe house grounds, you must wind through the historic Atgeld Gardens, homes the US government built for Word War II Black defense workers.

Later, the area became known as the toxic donut, with it being circled by toxic industrial sites. It is also where Hazel Johnson, via her crusade for fairness, earned her stripes as the Mother of the Environmental Justice Movement.

The overlapping of African American history could not escape the two-hour tour even as McClellan came to a close. Tom Shepherd, Secretary and Lead Organizer of the Little Calumet River Underground Railroad Project, could not resist adding that 7 miles away, along the river, is historic Robbins, Illinois, which is home to many achievements including the nation’s first Black airport and more.

Notes:

The Obama Presidential Center is expected to draw more traffic to this and other sites including:

5 minutes to the DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center

15 minutes to Pullman National Monument

20 minutes to Chicago’s Finest Marina and Underground Railroad Site Memorial

30 minutes to Hard Rock Casino – Northern Indiana @ Gary

35 minutes to Miller Beach/Marquette Park and the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore in Gary

From Port of Harlem Archives:

Ed Dwight - The First Black Qualified as an Astronaut Gateway to Freedom sculpturer

Eerily, McClellan and I amusingly noted that many now associate the Dutch with the anti-Blackness of apartheid in South Africa and Germans with anti-Black Naziism.

Then 16-year-old Quarlls started her journey in St. Louis, where she was enslaved. She escaped in 1842, headed north to Milwaukee, south to Chicago, and around Lake Michigan via what would become Gary before arriving in Detroit to cross the Detroit River into Canada and freedom.

The road she traveled from Chicago to Detroit, the Detroit to Chicago Road, was built in 1824 after the U.S. government negotiated a right of way with the Native communities. When building the road, the Americans generally followed trails Native Americans had used for centuries. Present-day Interstate 94 generally parallels the Detroit-Chicago Road and the ancient trails.

Similar to the Ton family, who were Dutch immigrants, many of the early station managers who helped Quarlls were newly arrived Germans. Eerily, McClellan and I amusingly noted that many now associate the Dutch with the anti-Blackness of apartheid in South Africa and Germans with anti-Black Naziism.

On the opposite site of the former safe house is a closed Chicago dump. Even to get to the former safe house grounds, you must wind through the historic Atgeld Gardens, homes the US government built for Word War II Black defense workers.

Later, the area became known as the toxic donut, with it being circled by toxic industrial sites. It is also where Hazel Johnson, via her crusade for fairness, earned her stripes as the Mother of the Environmental Justice Movement.

The overlapping of African American history could not escape the two-hour tour even as McClellan came to a close. Tom Shepherd, Secretary and Lead Organizer of the Little Calumet River Underground Railroad Project, could not resist adding that 7 miles away, along the river, is historic Robbins, Illinois, which is home to many achievements including the nation’s first Black airport and more.

Notes:

The Obama Presidential Center is expected to draw more traffic to this and other sites including:

5 minutes to the DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center

15 minutes to Pullman National Monument

20 minutes to Chicago’s Finest Marina and Underground Railroad Site Memorial

30 minutes to Hard Rock Casino – Northern Indiana @ Gary

35 minutes to Miller Beach/Marquette Park and the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore in Gary

From Port of Harlem Archives:

Ed Dwight - The First Black Qualified as an Astronaut Gateway to Freedom sculpturer

Advertisers | Contact Us | Events | Links | Media Kit | Our Company | Payments Pier

Press Room | Print Cover Stories Archives | Electronic Issues and Talk Radio Archives | Writer's Guidelines