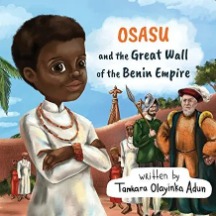

Tamkara Olayinka Adun’s "Osasu and the Great Wall of the Benin Empire" does affirm the declaration of one of its blurbs: “A must-read for every child and teen interested in untold histories.” Adun’s retelling of the fall of the Benin Empire and the attendant Benin Massacre of 1897 is clear, cogent, and creative. The story, told from a third-person perspective, follows Osasu, son of a Benin bronze artist.

Through Osasu’s interaction with his father, readers learn about some of the arts and customs of the Benin Empire. The Benin Empire flourished from the 900s until its fall to the force of the British Empire in 1897 during the reign of Oba Ovonramwen Nogbaisi.

The men are led to Oba Nogbaisi who welcomes them and throws a lavish festival in their honor before they leave for Britain. But they soon return to attack the Empire.

At the time of the story, presumably sometime close to 1888, Osasu is at the market when he notices, like others, the arrival of some European men. The men are led to Oba Nogbaisi who welcomes them and throws a lavish festival in their honor before they leave for Britain. But they soon return to attack the Empire. The story ends with Osasu’s vow to rebuild the wall destroyed by the British.

The story told in Osasu and the Great Wall of the Benin Empire does not focus solely on the monarch or the political drama that culminated in the fall of the Empire. Rather, it offers a snapshot of the social culture of the Edo people. And that is fine, insofar as the aim of the book is to introduce the young readers to the powerful kingdom.

Osasu and the Great Wall of the Benin Empire

The greatest strength of this book is its clear articulation of the historical detail that it presents which allows several teachable moments. For instance, there is a reference to streetlights in the Benin Empire. This reference is factual, and it is an opportunity to introduce readers to African civilizations and technologies and therefore decenter Western technology as the first and greatest markers of human innovation.

There is just the right amount of detail for a text meant for young readers. Teachers who find the text thin on history will find useful material in the Author’s Notes which presents a succinct history of the kingdom.

This story will undoubtedly elicit questions from curious young readers: Why was it so easy for the British to overcome Benin? What did Nogbaisi do to protect his people? Where was Nogbaisi during the invasion? Why did the British take over Benin in such a cruel manner?

These questions are taken up in more depth in other literary texts which may be too complex for young readers but will help teachers to construct background knowledge. In addition to encyclopedic texts, two resources to consult will be Ovonramwen Nogbaisi (1974), a historical tragedy written by Ola Rotimi, and Invasion 1897, a 2014 film directed by Lancelot Imasuen.

To echo again one of its blurbs, Adun’s Osasu and the Great Wall of the Benin Empire is a “must-read for every child and teen interested in untold histories.” But it must be added that even as such, the text merely whets the appetite of such a child and teen—and the author concedes so. If this text is read in a class of teenagers, it should be supplemented with material that can provide some more historical detail.

There is just the right amount of detail for a text meant for young readers. Teachers who find the text thin on history will find useful material in the Author’s Notes which presents a succinct history of the kingdom.

This story will undoubtedly elicit questions from curious young readers: Why was it so easy for the British to overcome Benin? What did Nogbaisi do to protect his people? Where was Nogbaisi during the invasion? Why did the British take over Benin in such a cruel manner?

These questions are taken up in more depth in other literary texts which may be too complex for young readers but will help teachers to construct background knowledge. In addition to encyclopedic texts, two resources to consult will be Ovonramwen Nogbaisi (1974), a historical tragedy written by Ola Rotimi, and Invasion 1897, a 2014 film directed by Lancelot Imasuen.

To echo again one of its blurbs, Adun’s Osasu and the Great Wall of the Benin Empire is a “must-read for every child and teen interested in untold histories.” But it must be added that even as such, the text merely whets the appetite of such a child and teen—and the author concedes so. If this text is read in a class of teenagers, it should be supplemented with material that can provide some more historical detail.

Advertisers | Contact Us | Events | Links | Media Kit | Our Company | Payments Pier

Press Room | Print Cover Stories Archives | Electronic Issues and Talk Radio Archives | Writer's Guidelines