In 1996, Richard Miller and Isaac Prentice, members of the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society’s (AAHGS) Prince George’s County, Maryland chapter, along with Prentice’s friend John Craig were the first to tell the story of Chaplain Henry Vinton Plummer’s 1894 dishonorable discharge from the US Army. The story came as a surprise to the Reverend L. Jerome Fowler, a Plummer descendent who often speaks about his family and its connection to the Riversdale Plantation in what is now Riverdale, Maryland in suburban Washington, DC.

Fowler did not know that his great-granduncle was the first African American chaplain in the US Regular Army and that there is a thick legal dossier documenting his military experience. As Reverend Fowler and others read the court martial transcript for the first time, they questioned the guilty verdict.

In 2001, AAHGS members Miller, Prentice, and Carolyn Corpening Rowe joined with politicians, educators, military men, and Plummer family members to petition for changing Plummer’s discharge from dishonorable to honorable. In 2005, more than one-hundred years beyond the statute of limitations, the Committee to Clear Chaplain Plummer achieved its goal.

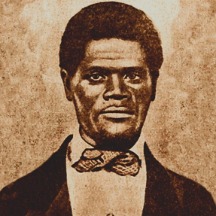

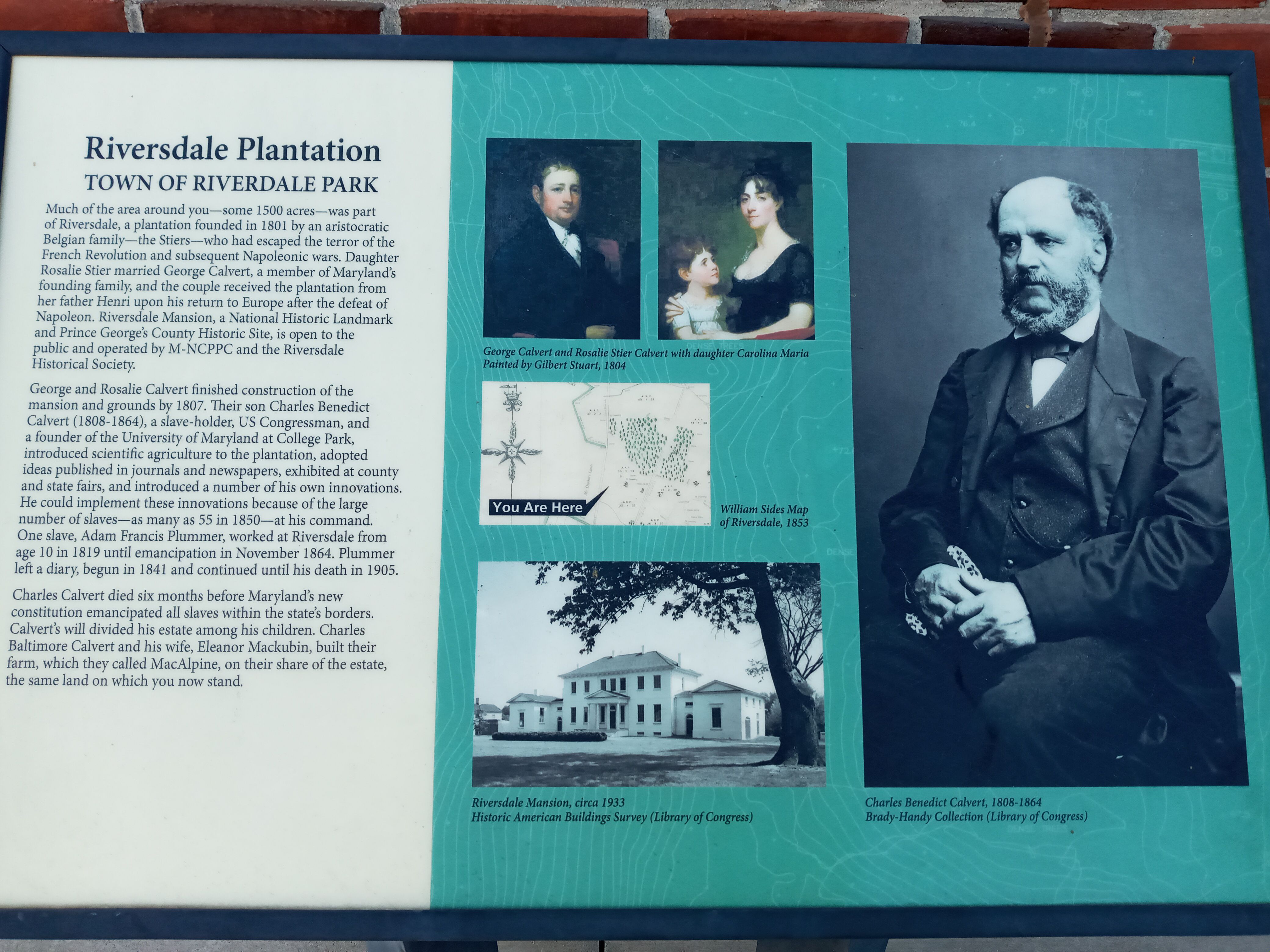

Henry, the future Chaplain, was the oldest son of Adam Francis Plummer (1819–1905) and Emily Saunders Plummer (c.1815–1876). Adam was enslaved at Riversdale Plantation, owned by Lord Baltimore descendant George Calvert and his wife Rosalie Stier Calvert. Emily, toiled in bondage eight miles away at Three Sisters Plantation.

Adam worked for young Charles Benedict Calvert, who would eventually found the Maryland Agricultural College (now the University of Maryland) . . .

Eight of the couple’s nine children survived to adulthood with remarkable life stories attesting to the resilience, faith, and values of an enslaved family. They endured separations and auctions, succeeded and failed at escape attempts, founded a church, and retrieved one daughter sold south.

Patriarch Adam was literate. He left a record of his dynamic life stories in a diary recording significant family events, money borrowed and repaid, and an inventory of his wife’s cabin. Recovered from a relative’s attic in 2001, his long-lost diary was donated to the Smithsonian’s Anacostia Community Museum. The diary and a transcript is on the museum’s website.

Adam and Emily’s youngest daughter, Nellie Arnold Plummer, self-published a spiritual memoir in 1927, “Out of the Depths, or The Triumph of the Cross.” She recounted her family history in honor of her parents and oldest brother’s and sister’s lives in slavery. With an introduction by Joanne M. Braxton, the book was reprinted in 1997 (New York: G. K. Hall, African American Women Writers, 1910–1940 series, Henry Louis Gates Jr., general editor). The book is the source for much of the family’s history:

Adam worked for young Charles Benedict Calvert, who would eventually found the Maryland Agricultural College (now the University of Maryland), serve in state and federal government positions, and headed up what we now know as the Department of Agriculture. Nellie portrays the two as enjoying a mutually respectful relationship.

After marrying Emily in a Washington, DC, church in 1841, Adam walked weekends to visit her and their growing family at Three Sisters Plantation.

Their failed escape attempt in 1845 led to punishment for Emily and her eventual sale along with three of their children (Henry, Julia, and Saunders) to Colonel Gilbert Livingston Thompson and his wife May Ann. Emily and the children were moved to Meridian Hill in Washington, DC, and then to Howard County, Maryland, with the Thompsons. Two of the children, Miranda and Elias, remained at Three Sisters.

Adam apparently received no punishment, and he continued to visit his family when he could. The family grew, adding Margaret and twins Robert and Nellie. Marjory Ellen Rose died in infancy.

The Plummers, 1815-Forward

Praising the Past

As best she could, Emily protected her children from their cruel master, Colonel Thompson. He kicked and swore at them, and disliked Emily’s spirited responses, for she “defended her little children from his fierce and brutal attacks, by telling them to flee. ‘Run, run,’ she would say. ‘Don’t let him kill you’” (Out of the Depths, 41).

Like many plantation owners, Thompson was cash poor and unable to pay the costs to retrieve his property. Finally, a judge released Emily and children to Adam, who took them to his Riversdale cabin.

On one occasion, he complained about her objections to his punishing her daughter Julia, and she struck him with a plucked goose. Meanwhile, oldest daughter Miranda was sold south to New Orleans. When President Lincoln emancipated the enslaved in Washington, DC, in 1862, Henry fled to the District of Columbia and joined the Union Navy. Elias, too, made his way into DC. Finally, a distraught Emily fled from the Thompson home with her remaining children in 1863, only to be caught and jailed in Baltimore.

Like many plantation owners, Thompson was cash poor and unable to pay the costs to retrieve his property. Finally, a judge released Emily and children to Adam, who took them to his Riversdale cabin. Emily and the older children secured paying jobs, and, when the Civil War ended, Henry and Elias returned to live with their parents in Maryland. Adam insisted that all family members work and earn money to retrieve Miranda from New Orleans and to purchase a family homestead.

In 1866, Henry journeyed to Louisiana and returned with Miranda, now a widow with a young son. In gratitude, she immediately founded St. Paul Baptist Church.

Between 1868 and 1870, Adam purchased a ten-acre plot, naming it “Mount Rose.” Each of the eight Plummer children made their way after obtaining freedom. Henry, Elias, Robert, and Nellie attended Wayland Seminary in Washington, DC. Henry and Elias became pastors, while Elias was also a teacher. Robert continued his studies at Howard University and became a pharmacist; Nellie became a teacher. Saunders pursued his love of horses, and Margaret became a homemaker and eventually her father Adam’s caregiver. Sadly, Elias who was left at Three Sisters when he was five and allowed to see his mother just twice in ten years, ultimately chose to distance himself from the family.

Emily enjoyed her family and rejoiced in Henry’s success as pastor of the church that Miranda founded. When he preached his first sermon on 2 January 1876, she said, “Son, you have preached my funeral sermon! God has given me all for which I have asked him! My cup runneth over! To think that my son has been elevated to the pulpit, and I have sat under his voice today” (Out of the Depths, 122). Within days, pneumonia set in and Emily died on 17 January 1876.

In 2018, Emily was inducted into the Maryland Women’s Hall of Fame for her dedication to family and faith, and as a representative of all the enslaved Maryland women whose stories we will never hear. After a long and finally satisfying life, Adam died on 13 December 1905 at Mount Rose surrounded by all his children, except Elias. Since 2001, the Plummer descendants have gathered regularly in Maryland, Kansas, and Michigan to celebrate their heritage.

Note: This article first appeared in AAHGS News, The Bi-Monthly Newsletter of the Afro-American Historical & Genealogical Society, Inc.

See Also:

Afro-American Historical & Genealogical Society on Overcoming 1890 Census Hurdle

with Natonne Kemp

When Should You Use DNA Testing to Confirm Family History

with LaBrenda Garret-Nelson

To attend the virtual annual AAHGS conference, register now.

Like many plantation owners, Thompson was cash poor and unable to pay the costs to retrieve his property. Finally, a judge released Emily and children to Adam, who took them to his Riversdale cabin.

On one occasion, he complained about her objections to his punishing her daughter Julia, and she struck him with a plucked goose. Meanwhile, oldest daughter Miranda was sold south to New Orleans. When President Lincoln emancipated the enslaved in Washington, DC, in 1862, Henry fled to the District of Columbia and joined the Union Navy. Elias, too, made his way into DC. Finally, a distraught Emily fled from the Thompson home with her remaining children in 1863, only to be caught and jailed in Baltimore.

Like many plantation owners, Thompson was cash poor and unable to pay the costs to retrieve his property. Finally, a judge released Emily and children to Adam, who took them to his Riversdale cabin. Emily and the older children secured paying jobs, and, when the Civil War ended, Henry and Elias returned to live with their parents in Maryland. Adam insisted that all family members work and earn money to retrieve Miranda from New Orleans and to purchase a family homestead.

In 1866, Henry journeyed to Louisiana and returned with Miranda, now a widow with a young son. In gratitude, she immediately founded St. Paul Baptist Church.

Between 1868 and 1870, Adam purchased a ten-acre plot, naming it “Mount Rose.” Each of the eight Plummer children made their way after obtaining freedom. Henry, Elias, Robert, and Nellie attended Wayland Seminary in Washington, DC. Henry and Elias became pastors, while Elias was also a teacher. Robert continued his studies at Howard University and became a pharmacist; Nellie became a teacher. Saunders pursued his love of horses, and Margaret became a homemaker and eventually her father Adam’s caregiver. Sadly, Elias who was left at Three Sisters when he was five and allowed to see his mother just twice in ten years, ultimately chose to distance himself from the family.

Emily enjoyed her family and rejoiced in Henry’s success as pastor of the church that Miranda founded. When he preached his first sermon on 2 January 1876, she said, “Son, you have preached my funeral sermon! God has given me all for which I have asked him! My cup runneth over! To think that my son has been elevated to the pulpit, and I have sat under his voice today” (Out of the Depths, 122). Within days, pneumonia set in and Emily died on 17 January 1876.

In 2018, Emily was inducted into the Maryland Women’s Hall of Fame for her dedication to family and faith, and as a representative of all the enslaved Maryland women whose stories we will never hear. After a long and finally satisfying life, Adam died on 13 December 1905 at Mount Rose surrounded by all his children, except Elias. Since 2001, the Plummer descendants have gathered regularly in Maryland, Kansas, and Michigan to celebrate their heritage.

Note: This article first appeared in AAHGS News, The Bi-Monthly Newsletter of the Afro-American Historical & Genealogical Society, Inc.

See Also:

Afro-American Historical & Genealogical Society on Overcoming 1890 Census Hurdle

with Natonne Kemp

When Should You Use DNA Testing to Confirm Family History

with LaBrenda Garret-Nelson

To attend the virtual annual AAHGS conference, register now.

Advertisers | Contact Us | Events | Links | Media Kit | Our Company | Payments Pier

Press Room | Print Cover Stories Archives | Electronic Issues and Talk Radio Archives | Writer's Guidelines