Robert Lawrence, Jr. (1967) was the first Black astronaut, but he died in a plane crash during a training flight in 1969 and never made it into space. Guion Bluford (1983) became the first Black American astronaut to travel in space; Mea Jemison (1992) became the first Black female astronaut. Frederick Gregory (1998) was the first African-American shuttle commander. But, it was Kansas City, Kansas native Ed Dwight who paved their way.

“In 1961, I got a letter in the mail asking me if I wanted to be an astronaut,” recalls Dwight as we sat in his Denver studio. The letter was a result of a promise President Kennedy made to Urban League President Whitney Young to accept a Black in the astronaut training program. But according to the authors of “The Real Stuff,” the prevailing belief was that the space program would select a Negro, “but [he] would never fly for NASA.”

Interestingly, flying was not Dwight’s childhood dream. “I have been creating art since I was in preschool,” says Dwight, who has since made his mark as an outstanding sculpturer. Only after his father “gave him the word,” that he was not going to be a struggling artist dependent upon his parents did Dwight begin studying the math and science needed to graduate from Arizona State University’s aeronautical engineering school.

After completing Experimental Test Pilot School and the Aerospace Research Pilot course, he became the first Black qualified as an astronaut. However, the politics of the day prevented the United Stated from sending its million-dollar investment into space.

“If it was important enough to this country to have a minority early in space than the logical guy was Dwight,” says Thomas McElmory in “Right Stuff.” McElmory was the Deputy Commandant of Aerospace Research Pilots School when Dwight was a student. The Russians sent the first Black, Amaldo Tamayo-Mendex of Cuba, into space in 1980, and simply said, “He (Dwight) was rejected for astronaut duty because he is a Negro.”

Dwight likens his experience to that of Henry O. Flipper, the groundbreaking first Black West Point graduate, who the U.S. government court martialed. After the government dismissed him, Flipper went on and earned respect as a surveyor and interpreter.

But according to the authors of “The Real Stuff,” the prevailing belief was that the space program would select a Negro, “but [he] would never fly for NASA.”

After many tribulations, Dwight side stepped Flipper’s fate and earned a good conduct discharge. However, like Flipper, he has gone on and earned respect in another field.

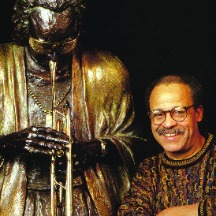

In order to capture his boyhood dream, Dwight returned to school and earned a master’s degree in sculpture. Today, his company, Ed Dwight Studios, is one of the largest single artist production and marketing facilities in the Western U.S. He has unveiled many major monuments including the first bi-national monument in Detroit, MI and Windsor, Canada dedicated to the International Underground Railroad Movement and the African-American History Monument on the Capitol Grounds in Columbia, SC.

Also like Flipper, Dwight is planning to write an autobiography. In the meantime, Dwight continues to get inspiration from a DVD on Flipper’s life. He added, “I sit and watch it all the time.”