My seven-week journey took me to Australia, Papua New Guinea, The Solomon Islands, and New Zealand, where the original inhabitants are Malanesians, who are black-skinned, or Polynesians, who are brown-skinned. Today, most of the citizens of Australia and New Zealand are descendants of Europeans.

After my four-hour flight from Washington, D.C. to Los Angeles, followed by my long, but pleasant 13-hour transpacific flight from Los Angeles to Cairns, Australia, I spent the first five days in the resort town of Cairns. When the Europeans arrived in Australia in 1770, they called the people on the mainland Aborigines. The story of the black-skinned Aborigines is similar to that of Native Americans. Europeans took the best land, killed the Aborigines, and didn’t grant them the right to vote until 1962.

Most of the Aborigines that I saw in Cairns were derelicts and alcoholics. So, I flew on to cosmopolitan Darwin in the Northern Territories, rented a jeep, and took a three-hour drive to the Kakadu National Park area where many Aborigines live in settlements. There I expected to see a more diverse group of them.

While in the area, I saw several Aborigines and followed them into a recreation center. The center is what an American would label a bar and I got my first taste of Australian segregation. The Australians of British descent mainly occupied the side of the bar that was set-up more like an attractive sit-down restaurant. The Aborigines occupied the dingy side with a bar and a worn pool table. After I digested what I saw, I figured that legal segregation in the U.S. must have created similar scenes.

Before leaving America, I knew that I needed permission from Aborigine elders to visit their villages. I was hoping that I would be able make the connections upon arrival. Instead, either flooded roads or no trespassing signs prevented me from reaching my goal.

My itinerary had me back in Cairns just in time for me to witness Cyclone Steve. I stocked up on cans of fish, dried fruit, and bottled water, and stayed close to my hotel. Having read about the devastation caused by Cyclone Tracy in 1974, I expected disaster. The television, pouring rain, and gusting wind provided me comfort as I fell asleep. However, much to my amazement, I awoke to minimal damage.

Though Steve left Cairns and my trip intact, I knew it was time for me to leave Australia when I was buying fabric in a store. At the counter, a clerk of British descent looked at me and asked, “Where are you from? When I said that I was from the U.S., he replied knowing that I was not an Aborigine. “No wonder you look so civilized.” I left the fabric in the store and said to him “I will show you how civilized I am, I going to walk out of here and not do what is on my mind!”

I moved on to Port Moresby, the capital of Papua New Guinea. When the Portuguese first arrived in 1777, the name they gave the island translates into English as “Island of the fuzzy hairs.” The Dutch later called it New Guinea, because the locals reminded them of the people in Guinea, West Africa.

Port Moresby has a well-earned reputation of being crime ridden. The local people constantly warned me not to enter certain areas and to be aware of “rascals” or street gangs. However, I nicknamed it “city of blood” for the red saliva found everywhere. The saliva is the result of the round greenish-orange betel nut that many in the South Pacific use like chewing tobacco. It has a narcotic effect and turns the chewer’s saliva red. After three days, I was glad to head to the Trobriand Islands, which is a part of New Guinea and has the reputation of being the “Island of Love.”

The sexual customs on the Island are different from many other places. Teenagers are encouraged to have as many sexual partners as they choose until marriage. In June, during the celebration honoring the harvest of yams, even married couples, subject to mutual agreement, allow themselves to have a fling or two.

Surviving the South Pacific

I also took a side trip to Taro to see what others have reported to be some of the darkest people on earth. They were very dark, blue black. Few tourists come to this small island. It does not have a hotel, so I stayed in a government house with lots of mosquitoes. Taro also has no restaurants, limited electricity, and one small general store. With no plane scheduled to arrive until three days after I arrived, I had no choice, but to survive on hard saltine crackers, canned fish, and hot soda.

The sexual customs on the Island are different from many other places. Teenagers are encouraged to have as many sexual partners as they choose until marriage.

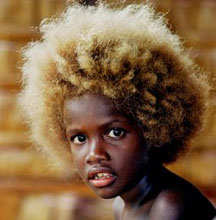

After a short return to Port Moresby, I spent the next 17 days in The Solomon Islands. Surprisingly, the taxi driver that picked me up at the airport was the first of many who loved country and western music, and boxing. When he dropped me off at my hotel, I discovered that it was next to a school with plenty of children of color with naturally blond hair. Reality set in. “Yea, it’s real,” I said to myself. I just looked at them in amazement.

Later, after my return home, I would recall this reality after hearing the story of Janel Rankins, a 21-year-old African-American woman in Willamsburg, VA. Her supervisor would not let her wear dyed blond hair to work because he thought blond hair on a Black person looked unnatural.

Before leaving The Solomon Islands, I had to visit Skull Island. Before the trip, I had read much about Islanders who were once cannibals and would ritually take their victims’ skulls to the island. On the island, that is the size of a large living room, the cannibals had neatly stacked the human skulls in a loosely made circle.

After making connections through Port Moresby and Brisbane, Australia, I landed in New Zealand. Its European descendants seemed so color blind. Only after much conversation, did they ask where I was from. It was also interesting to learn that the original inhabitants of the country, the brown-skinned Maoris, identify with the American Black Power movement of the 1960s.

The country’s landscape is beautiful, one of the most colorful that I have ever seen. I spent several days roaming around in a jeep taking pictures of colorful treetop mountains, aqua blue waterfalls, and rushing geysers that smelt like rotten eggs before returning to Cairns for my flight home.

Not a great deal of African-Americans have made it to the South Pacific since the many who fought there during World War II, so people didn’t quickly associate me as being of the same kind as the Black soldiers. Since I am not White, they did not think I was an American.

Since I am over six-feet tall and most Malanesians and Polynesians are relatively short, most of them knew that I was not one of them. Most would ask if I was born in Africa, like some of the other Blacks living in the area. Anyway, we bonded as brothers and sisters of color.

One day, I was walking a New Zealand street when a person of British descent shouted to a group of Maoris, “There goes your brother!” The Maoris came over and embraced me. The other day, I get a letter from a Solomon Islander. The letter warmly stated, “Dear Colour, how are you? Don’t forget to tell your friends that Black people are here.”