Black families have a hard time building generational wealth, as opposed to many whites, who inherited wealth through ancestors’ investments in stocks, bonds, real estate, and other ventures. Black families primarily build wealth through purchasing homes. If they can hold on to their homes and the land on which they sit, their wealth is in home equity. But from the end of enslavement, through Reconstruction, Jim Crow, segregation, and present-day redlining and gentrification, Black people struggle to find and purchase affordable homes in neighborhoods they choose.

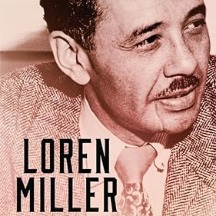

At least one barrier to Black home ownership was knocked down thanks in large part to Loren Miller, a little-known Black “Renaissance man” from California. His biographer, Amina Hassan, Ph.D., also a Californian, thought more people should know about Miller and his significant civil rights contributions. Her hardback book, “Loren Miller, Civil Rights Attorney and Journalist” was published in 2015. History buffs and others who just love a good story will have another chance to read it. The publisher released it in paperback in February.

Loren Miller and 21 other Black people, among them poet Langston Hughes, were invited to the Soviet Union to co-write a film about “Negro life” in the U.S.

The book details Miller’s outstanding legal work as the NAACP Chief Counsel in Shelley v. Kraemer. In 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the case that legal enforcement of racially restrictive covenants was unconstitutional. Restrictive covenants were agreements between whites that they would never sell their homes to “minorities.” The high court ruling opened home buying nationally for non-Whites.

In addition to the restrictive covenants case, Miller represented Japanese Americans in California when whites took their land and sent them to detention camps. They equated Japanese Americans with the country Japan which was fighting the U.S. during World War II. Miller eventually became a columnist, editor, and owner of The California Eagle, a Black newspaper. Years later he founded another Black newspaper, The Los Angeles Sentinel.

Hassan not only describes Miller’s journalistic and legal accomplishments but places them within the context of what was going on in the U.S. and the world which shaped his political outlook. His family’s fight against enslavement was one such factor. Miller’s father, John Bird Miller, had been enslaved. Thomas Miller, Loren’s grandfather, married an enslaved woman, Jane Gee, who lived on the same Missouri plantation. The couple escaped from Missouri to Kansas. Then Thomas Miller fearlessly sneaked back into Missouri to free more relatives.

Hassan shows us that like his grandfather, Loren Miller was determined to achieve, despite bigotry. Raised with six siblings in rural poverty, Miller turned to books as his “escape.” His love of reading led to a passion for creative writing. In 1926, Miller, then a Howard University student, won a $75 cash prize from Crisis, the NAACP’s magazine, in its writing contest. His essay, “College,” reveals Miller’s conflicted emotions concerning his dream of becoming a writer, while knowing a legal career was more financially lucrative. “You plunge into law,” Miller wrote. “You secretly loathe it. You still find yourself writing little sketches, tragic bits of verse, but you repress them. . .”

Another writing opportunity came to Miller in 1932. He and 21 other Black people, among them poet Langston Hughes, were invited to the Soviet Union to co-write a film about “Negro life” in the U.S. The group spent months in Russia, frustrated with nothing to do. Hassan describes the hilarious miscommunications between the group and the Russians, who spoke little English, and knew nothing about African Americans. An early draft of a script, written by a Russian, depicted a rich white Southern man waltzing with his Black maid.

The Soviet Union visit energized Miller, a committed Marxist. Hassan surmises that his politics might have stalled Miller’s legal career. Miller ultimately became a California municipal judge. Hassan writes that Miller’s dry wit and “acid tongue” put off some people. Due to his views and his racial solidarity, the FBI “investigated” Miller until the day he died, even demanding a copy of his death certificate. Miller died on July 14, 1967. July 14 is “Bastille Day”, when French revolutionaries stormed an old fort in 1789 and freed prisoners. “(It’s) a fitting coincidence,” writes Hassan, “for a man dedicated to storming the hush-hush of courtroom injustice.”