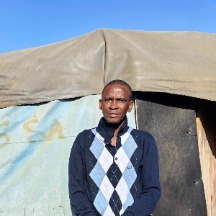

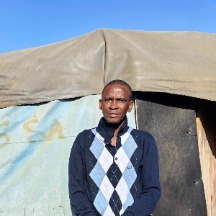

Pitso Molahlehi is fifty-three years old, and has spent most of his adult life working in South Africa’s gold and diamond mines. He was born in the neighbouring Republic of Lesotho, and like many men from his country, he crossed the border into South Africa to work for mining companies so he can earn a living.

He first worked in a gold mine in Johannesburg. Later, when his family migrated to South Africa in search of a better life, he moved to another gold mine called Vaal Reefs where he worked for two years before resigning with the intention of going back to school. “I wanted a better life,” Molahlehi said.

But “Black tax” quickly caught up with him. He had financial obligations to his family. If you stop working and go back to school, who is going to take care of your parents? Who will take your younger siblings through school? These were terrifying questions that needed urgent answers from the then young man with bright dreams.

“We’re bothering no one. The soil we’re sieving through has been discarded. It’s rubbish. In actual sense, we’re deriving our livelihood from rubbish.”

Molahlehi’s life had been spent searching for minerals and when he returned to work, that is where he went. He went to work in small opencast mines in South Africa’s diamond fields. He later joined his friends who were informal diamond miners in Kimberley.

The City of Diamonds, as Kimberley is known worldwide, has attracted people from near and far - - all pursuing the shining stone. Following the discovery of diamonds on a farm near Colesberg, not too far from Kimberley in 1871, approximately fifty thousand men dug what later came to be known as The Big Hole, between 1871 and 1914.

According to official sources at the Big Hole Museum, the hole was dug with picks and shovels and produced 2 722 kilograms of diamonds after excavating more than twenty-two tons of earth. The Big Hole, at the moment, is the biggest human-made excavation in the world at the depth of 214 metres, surface area of 17 hectares and the perimetre of 1,6 kilometres.

Diamonds Are Our Only Hope

Features

Although mining operations at the famous Big Hole were halted during the onset of World War I, diamond mining has never ceased in Kimberley and the surrounding towns and farms.

In the past few decades men, mainly the ones who have been retrenched after working at diamond mines for years, have been drawn to Kimberley to sieve through the soil that has been discarded by mining companies. They came in search of diamonds.

Their tools of trade were not big earth-moving machines, but picks, shovels, sieves and plastic buckets to carry soil. Their activities were illegal and they often found themselves in confrontation with the public order police.

“After many battles, the authorities realised that we were going nowhere. They would come and shoot at us with rubber bullets and teargas and the following day we would be back, searching for the diamonds because we needed to make a living,” Molahlehi said.

“We’re bothering no one. The soil we’re sieving through has been discarded. It’s rubbish. In actual sense, we’re deriving our livelihood from rubbish.”

After many meetings between the miners, government and mining companies, about eight hundred illegal informal miners were issued with permits to sieve through the soil and possess diamonds. “Now we’re no longer ‘illegal’. We’re just ‘informal’. No one will arrest me for possessing a diamond. It’s not a crime. Kimberley is the last place we can come to. Diamonds are our last hope against poverty,” Molahlehi says.

Following the issuing of permits, a shanty town sprung up on Samaria Road in the outskirts of Kimberley. Once a forest, later heaps and heaps of soil from Kimberley’s underground diamond mines, Samaria Road is now a lively shanty town. Now and then the men of Samaria Road got lucky and found the shining stones, which they sold and sent money back home. Gradually the men went back home and returned to Kimberley with their families.

Many years on, Samaria Road resembles any shanty town, and has values that many communities can admire. “There is no crime in our community. If you commit a crime here, we arrest you and call the police. I can confidently tell you that men in this community don’t abuse women and children.”

In the past few decades men, mainly the ones who have been retrenched after working at diamond mines for years, have been drawn to Kimberley to sieve through the soil that has been discarded by mining companies. They came in search of diamonds.

Their tools of trade were not big earth-moving machines, but picks, shovels, sieves and plastic buckets to carry soil. Their activities were illegal and they often found themselves in confrontation with the public order police.

“After many battles, the authorities realised that we were going nowhere. They would come and shoot at us with rubber bullets and teargas and the following day we would be back, searching for the diamonds because we needed to make a living,” Molahlehi said.

“We’re bothering no one. The soil we’re sieving through has been discarded. It’s rubbish. In actual sense, we’re deriving our livelihood from rubbish.”

After many meetings between the miners, government and mining companies, about eight hundred illegal informal miners were issued with permits to sieve through the soil and possess diamonds. “Now we’re no longer ‘illegal’. We’re just ‘informal’. No one will arrest me for possessing a diamond. It’s not a crime. Kimberley is the last place we can come to. Diamonds are our last hope against poverty,” Molahlehi says.

Following the issuing of permits, a shanty town sprung up on Samaria Road in the outskirts of Kimberley. Once a forest, later heaps and heaps of soil from Kimberley’s underground diamond mines, Samaria Road is now a lively shanty town. Now and then the men of Samaria Road got lucky and found the shining stones, which they sold and sent money back home. Gradually the men went back home and returned to Kimberley with their families.

Many years on, Samaria Road resembles any shanty town, and has values that many communities can admire. “There is no crime in our community. If you commit a crime here, we arrest you and call the police. I can confidently tell you that men in this community don’t abuse women and children.”

Advertisers | Contact Us | Events | Links | Media Kit | Our Company | Payments Pier

Press Room | Print Cover Stories Archives | Electronic Issues and Talk Radio Archives | Writer's Guidelines