By awarding the prizes, the Free Press promotes awareness and appreciation of contemporary Underground Railroad work to the general public, elected and other officials, governments, and key decision-makers by publicizing prizes and winners.

The prizes recognize and honor the most outstanding contributions to contemporary Underground Railroad work in three categories: leadership, preservation and advancement of knowledge.

The 2023 Prize for Leadership

Paul and Mary Liz Stewart have been busy promoting the Underground Railroad for 20 years since they cofounded Albany, New York’s Underground Railroad Education Center in 2003. Since then, the Center has created a strong program of education and research that celebrates and preserves the story of the Underground Railroad in Albany and the state’s Capital Region. The Center has identified local Underground Railroad historical figures and their activities and compiled a history of Albany’s Underground Railroad movement.

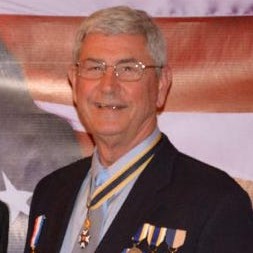

Paul & Mary Liz Stewart

The Stewarts have received multiple recognitions for their tireless work including being awarded the 2008 Underground Railroad Free Press Prize for Preservation for rediscovering and restoring the Stephen Myers safe-house in Albany. After restoring the home, the Stewarts furnished it in period and have used it since for office space and meetings.

Stephen Myers and His Safe-house Home

But over the years as the organization’s programs expanded and more ideas for public engagement blossomed, space needs grew as the Center’s mission did. The Stewarts had their eye on the vacant lot next to Myers House and a much broader mission in mind but they needed larger fundraising to pull off what they had in mind.

By 2022, the work of the Underground Railroad Education Center and the dedication of the Stewarts had become widely admired in Albany and created a store of goodwill that could be called on to help get a new ambitious project launched. In store is a large building to house an interpretive center, expanded exhibits and providing a community space for children, guest speakers, artists and the public to learn about the area’s Underground Railroad history. In June, this dream became a reality when the state’s Assembly voted to grant the Underground Railroad Education Center $2 million to construct a building. The location will be on the vacant lot next to Myers House and construction is due to begin in 2024.

What Paul and Mary Liz Stewart have demonstrated in securing this grant is what dedicated leadership can accomplish in the greater Underground Railroad community. The Stewarts are the first two-time winners of a Free press prize, having been the recipients of the first Free Press Prize for Preservation in 2008.

The 2023 Prize for Preservation

After Ohio became a state in 1803, the challenge was on to better connect it to the original 13 Atlantic seaboard states by linking the expanding nation’s commerce across the Appalachian Range. The earliest effort was the National Road begun by the Jefferson administration that year, which widened trails leading from Cumberland, Maryland, to Vandalia, Illinois. The National Road is today’s US Route 40.

Seeking better cargo routes, the John Quincy Adams administration in 1828 began construction of the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal running alongside the Potomac River in Maryland. The plan was to push the canal over the Appalachians to Ohio. The canal operated by having its heavy barges towed by mules along a gravel towpath beside the canal. As the canal became reality, the towpath became one of the most frequented of all Underground Railroad routes, as freedom seekers coming north from Virginia either had to cross the towpath or flee along its northerly course. There are vivid first-person accounts by freedom seekers of their using the towpath at many places along it from its origin at Georgetown in Washington, DC, to its terminus at Cumberland, Maryland, 185 miles away.

In 2005, Dr. George Lewis, a retired veterinarian who lives in the tiny nearby hamlet of Lander, envisioned the restoration of the aqueduct and got to work mobilizing the National Park Service, elected officials, and private donors to make it happen. After a six-year blizzard of paperwork, on October 15, 2011, Dr. Lewis saw success as the reconstructed Catoctin Aqueduct, shown here, was dedicated by United States Senator Benjamin Cardin. Once again, the 185-mile Underground Railroad route along the canal was in one piece.

The 2023 Hortense Simmons Memorial Prize for the Advancement of Knowledge

Over the last 25 years or so that have experienced the marked revival of interest in the Underground Railroad, we have seen a number of well written books and deep research reports covering the Underground Railroad in local areas. Among these authors and their locales covered are William Switala (western Pennsylvania), Judith Wellman (north-central New York), Tom Calarco (New York City and Ohio), Owen Muelder (northwestern Illinois), Bryan Prince and Karolyn Frost (Canada), Mary Kay Ricketts (Washington, DC), Wendy Straight (western New York), Carol Mull (Michigan) and Vivian and Don Papson (Adirondacks). Most of these have been awarded Free Press’s Hortense Simmons Memorial Prize for the Advancement of Knowledge beginning with Calarco in 2008. Underground Railroad Free Press has published Guide to Freedom on the Underground Railroad in western Maryland.

Now comes Larry A. McClellan’s Onward to Chicago: Freedom Seekers and the Underground Railroad in Northeastern Illinois, in this case meaning Chicago and surrounding counties. Of all of the regional works on the Underground Railroad that we have seen, this book is perhaps the most detailed.

Through the end of the Civil War, Chicago’s Black population numbered only in the hundreds and the number of white Underground Railroad figures even fewer. Nevertheless, author McClellan finds them and details an exhaustive number of operatives and fugitives by name, and likewise a plethora of escape routes, safehouses, encounters, relationships and individual backgrounds, producing an extensive fine-grained portrait of the Underground Railroad as a living, breathing enterprise. This is the finest book yet of which we are aware for a close-up look at the Underground Railroad as it actually happened.

From Our Archives: Freedom Seeker Caroline Quarlls Walker with Larry A. McClellan