You may remember artist Whitfield Lovell’s images in the 2004 Pomegranate calendar or in museums from the Seattle Art Museum in Washington to the Studio Museum in Harlem. Now, the largest exhibition ever presented of Lovell’s work begins a national tour at the Boca Raton Museum of Art, February 15 to May 21. The South Florida museum is dedicating its entire first floor (7,500 square feet) for the multi-sensory showing.

After Boca Raton, “Whitfield Lovell: Passages” will then continue across six states throughout the American South and the Midwest. The exhibit will make stops in Richmond, VA; Little Rock, Cincinnati, Charlotte, and San Antonio.

One of Oprah Winfrey’s most treasured artworks is Lovell’s tableau (a group of models or motionless figures representing a scene from a story or from history) entitled “Having,” which she has kept in her office for decades. The wall-length charcoal image of two African American women features three vintage wood boxes filled with pennies, added by the artist.

“These women were early entrepreneurs. I have looked at this every day from my desk for years, to remind me and inspire me that, yes, it can be done,” Winfrey told the Los Angeles Times.

“I see history as being very much alive. One day, 100 years from now, people will be talking about us as history . . . "

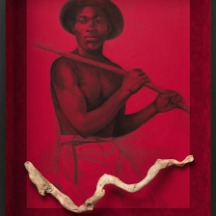

The Bronx, New York native is the recipient of a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship Genius Grant and is recognized as one of the world’s leading artistic interpreters of lost African American history. The internationally acclaimed artist is celebrated for his exquisitely hand-drawn, portraits - - many are life-sized, drawn with Conté crayons, from historic photos he finds of anonymous individuals.

The artist combines the portraits with intuitive assemblage of time-worn objects to raise universal questions about memory, American life, and reclaiming lost history that had been erased. The works in“Whitfield Lovell: Passages” are anchored by images of everyday African Americans, from the 1860s to the 1950s, between Reconstruction I and the start of Reconstruction II, a period of time the artist feels has been overlooked by the art world. “I see the so-called ‘anonymous’ people in these vintage photographs as being stand-ins for the ancestors I will never know,” says the descendent of the American South and Caribbean.

“I see history as being very much alive. One day, 100 years from now, people will be talking about us as history. The way I think about time is very different - - I don't think it really was very long ago that these things happened, it wasn’t that long ago that my grandmother’s grandmother was a slave,” added Lovell.

Growing up in The Bronx didn’t afford him many artist role models, but he decided he wanted to be an artist around age 13. “I didn’t have a lot of examples telling me that being an artist was something that I could do. When I came along in the art world, Black people didn't have gallery representation – we made art because we felt strongly that we had to make art. We found a way to make art,” added Lovell, who now has had many gallery showings including a 2016 “Whitfield Lovell: The Kin Series and Related Works" at the The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC.

Whitfield Lovell: Passages; USA Tour Starts

Artist Jay Durrah, whose portrait of George Washington Carver is in this issue’s “Inaugural George Washington Carver Day Celebration – February 1” article added, “As a portrait artist and lover of history, I admire the way Lovell's images exude the strength and resilience of everyday Black folk during extremely difficult periods in time. I also see a dignity and determination in his depictions, helping today's viewers to realize, we are a strong people.” (See Activities page in this issue for exhibits where Durrah will participate.)

The largest tableau in the “Visitation” installation is titled “Our Best,” measures twenty-two feet wide, and features life-sized charcoal drawings of people whose images are based on several historic photographs Lovell found in museums near Richmond. Dressed stylishly in elegant, turn-of-the-twentieth-century clothing, Lovell’s figures appear to hover just above the time-worn surfaces of the repurposed wood.

“As you approach the installation,” says Lovell, “you will hear the voice of a woman reciting the names of every resident who lived in this community – as a way of reminding us that these were all real people.”

They look strikingly successful, confident, and proud, assuming stances evocative of the entrepreneurial community of Jackson Ward. “As you approach the installation,” says Lovell, “you will hear the voice of a woman reciting the names of every resident who lived in this community – as a way of reminding us that these were all real people.”

Established in the Reconstruction I era and flourishing through the mid-twentieth century, Jackson Ward was home to an independent Black community that was successful economically, socially, civically, politically and artistically. Among its citizens were Maggie L. Walker, the country’s first Black woman bank president who founded the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank in 1903, and Sarah Garland Jones, the first Black woman physician in the United States.

The accompanying catalogue for the Lovell national tour, published by Rizzoli Electa, features groundbreaking scholarship and a fresh examination of Lovell’s work. In a video conversations with Lovell, recorded in 2020 during the peak of the pandemic, the artist is described as paying tribute to the daily lives of anonymous African Americans. Via his creations, Lovell provides these unknown figures with identity.

More About the Exhibition

Visitation: The Richmond Project

The largest tableau in the “Visitation” installation is titled “Our Best,” measures twenty-two feet wide, and features life-sized charcoal drawings of people whose images are based on several historic photographs Lovell found in museums near Richmond. Dressed stylishly in elegant, turn-of-the-twentieth-century clothing, Lovell’s figures appear to hover just above the time-worn surfaces of the repurposed wood.

“As you approach the installation,” says Lovell, “you will hear the voice of a woman reciting the names of every resident who lived in this community – as a way of reminding us that these were all real people.”

They look strikingly successful, confident, and proud, assuming stances evocative of the entrepreneurial community of Jackson Ward. “As you approach the installation,” says Lovell, “you will hear the voice of a woman reciting the names of every resident who lived in this community – as a way of reminding us that these were all real people.”

Established in the Reconstruction I era and flourishing through the mid-twentieth century, Jackson Ward was home to an independent Black community that was successful economically, socially, civically, politically and artistically. Among its citizens were Maggie L. Walker, the country’s first Black woman bank president who founded the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank in 1903, and Sarah Garland Jones, the first Black woman physician in the United States.

The accompanying catalogue for the Lovell national tour, published by Rizzoli Electa, features groundbreaking scholarship and a fresh examination of Lovell’s work. In a video conversations with Lovell, recorded in 2020 during the peak of the pandemic, the artist is described as paying tribute to the daily lives of anonymous African Americans. Via his creations, Lovell provides these unknown figures with identity.

Advertisers | Contact Us | Events | Links | Media Kit | Our Company | Payments Pier

Press Room | Print Cover Stories Archives | Electronic Issues and Talk Radio Archives | Writer's Guidelines