Enslaved Africans, living on Prince George’s County, Maryland’s vast tobacco plantations, were not freed by President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. Freedom came via the new state constitution of 1864, narrowly ratified only a few months before Congress enacted the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery as an institution in all U.S. states and territories. The constitution also called for the creation of the state’s first state funded public school system, making public schools for colored students possible, albeit unfunded.

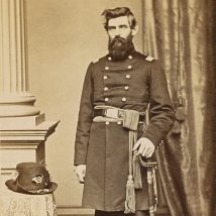

After the American Civil War, The Freedmen’s Bureau appointed Reverend General John Kimball of Massachusetts as Superintendent of Schools for the District of Columbia region in August 1866. His jurisdiction included Prince George’s County, currently the nation’s wealthiest majority Black county in America. Kimball, like his counterparts in other states, was tasked with establishing, supervising, and maintaining Freedmen schools. The effort to provide equal educational opportunities for Blacks was a struggle then and is now.

Kimball worked on the behalf of children and adults eager to learn to read and write after years of being prohibited from doing so during slavery - if not by Maryland law, then by intimidation.

Monthly reports from agents and teachers assigned to the eleven Bureau schools in Prince George’s between 1865 and 1870 documented student enrollment, expenditures for teacher salaries, and instructional materials (subsequently sold to students). Letters, with endorsements, to and from Reverend Kimball disclose even more information about the challenges with logistics and local activities, and other disputes.

As early as 1861, as Union troops advanced on Confederate armies, charitable organizations, based in New England, responded to the fervent appeals of Edward L. Pierce, also of Massachusetts, and others to contribute funds to provide for the basic needs of liberated, but destitute freedmen.

Kimball worked on the behalf of children and adults eager to learn to read and write after years of being prohibited from doing so during slavery - if not by Maryland law, then by intimidation. Now, with the assistance and motivation of skilled teachers, they could acquire an education described by George Washington Carver as “the key to unlock the golden door of freedom.”

Initially, The Bureau’s educational efforts in Prince George’s County were hampered by Maryland’s apprenticeship law. Contrary to the Civil Rights Act of 1866, Black school-age children could be taken into custody, often without the consent or even knowledge of their parents, to be “apprenticed” to their former owners or transported to other locations to work for an unspecified time. While this law was enforced, the Bureau’s minimum enrollment and attendance requirements often could not be met, making schools ineligible for financial support from the Bureau. The apprenticeship system was ended in 1868, only through the intense efforts of the Bureau.

Another major inhibitor to opening schools was a community’s inability to find appropriate housing for Bureau teachers. Local communities, especially in small, rural areas had difficulty fulfilling this important responsibility.

Racial biases quickly surfaced as well. Local debates often ensued as to the race and/or gender of the teacher being considered for assignment to a school. White powerbrokers often articulated these common precepts; denoting such rules of engagement as:

- White teachers cannot teach Black children

- White teachers cannot board with Black families

- Negro teachers, male or female, are not welcomed in the community

Black leaders countered such edicts with their own demands, arguing that only colored teachers should be assigned to a school for their children.

Once the terms and conditions of employment were enshrined and the dust settled, teachers, many from the northeast, were assigned to Bureau schools, and were successful, as these stories of two Bureau teachers in post-Civil War Prince George’s County illustrate:

Phineas P. Whitehouse (a New Hampshire native, was the teacher at the Bureau school in Rossville, Maryland from 1866 to 1870.) William E. Coffin, one of Boston's preeminent iron manufacturers, acquired Muirkirk Furnace in 1860 in what is now Beltsville, Maryland. His son, Charles, later renamed the company Muirkirk Ironworks, and set about to assure a quality of life for their workers and families that was not evident elsewhere. Coffin’s company established schools for the area’s colored children in 1864, shortly after slaves were emancipated in Maryland, and before the Bureau began operating in the state.

In one of many reports and letters to Reverend Kimball, Whitehouse wrote: “The colored pupils manifest a good degree of interest in the school and all feel proud of the beautiful new school house.” There, Whitehouse scheduled classes for white students in the morning, colored students in the afternoon, and an evening school for adult Negro ironworkers.

Whitehouse became the longest serving Bureau teacher in the county. The New England Freedmen Aid Society must be credited with supporting him and the school’s operations for most of, if not for the entire four years of its existence.

Charlotte Leach of Massachusetts, began teaching at the Magnolia Spring School in Forestville, Maryland on April 21, 1868. Leach had expressed enthusiasm about teaching at the school, despite the Bureau’s notices to her that it “was not currently able to pay her salary,” or assure a return ticket home after the school term ended in June. Undeterred, Leach arrived to find that the school house was not quite finished. To appease parents, anxious to send their children to school, a room was quickly arranged in another building to accommodate the fifty students. On May 27, 1868, Leach and her students moved to the new school house. The structure was finished, but there were no desks.

In reports to Reverend Kimball, Leach reported that “The success of her school faced extreme opposition from the local White population,” describing their sentiments towards the school as “strong prejudice against,” writes Omar Shareef Price, in his Morgan State University dissertation “Freedom, Faith and Education: The Formation and Legacy of Freedmen’s Bureau Schools of Prince George’s County, Maryland, 1866-1870.”

Despite these many trials, the Magnolia Spring students were some of the most advanced of any enrolled in Freedmen Schools in the county, according to Leach, who stated that all fifty of her pupils could “spell and read easy lessons: and fifteen were in ‘advanced readers.’”

Leach’s promising start at Magnolia Spring School was commended by Reverend Kimball and the community, but records do not reveal whether she was paid for her services. Moreover, the Bureau did not assure her of continued employment because she was not sponsored by a charitable organization. It is uncertain that Leach ever became a benefactor of one of those charities. What is certain is that she did not return to Magnolia Spring School in October that year.

Whitehouse, Leach, and others understood that the inherent promises of freedom – full citizenship, economic progress, and political power – could not be achieved without education. Yet, long after their passing, the struggle continues to find and dismantle several systemic laws and procedures that stymie equal educational opportunities.

Yet, with each rising sun, a new day begins. After years of legal wrangling and Republican Governor Larry Hogan’s “final” offer of $200 million in 2019, Maryland finally reached a $577 million settlement in 2021 to end a 15-year-old federal lawsuit that accused the state of providing inequitable resources to its four historically Black colleges and universities including Bowie State University in Prince George’s County.

Tales from Historic Mount Nebo Series

Is an ongoing series of stories about people connected to the historic Mount Nebo African American Episcopal Church, Cemetery, and/or Colored School in Bowie, Maryland. Subsequent articles in this Series:

Black Lives Matter in Death, Too – Mt. Nebo AME Preserves Historic Cemetery

Note: After the Freedmen’s Bureau schools closed in 1870, Mt. Nebo School for Colored Children opened in 1875.