and Food Access in Washington, DC.

Searching for Food Justice

Before desegregation, several Jewish owned grocery stores dotted the Northeast Washington neighborhood. Many of them belonged to a Jewish-dominated cooperative, The District Grocery Stores (DGS). For decades DGS competed against chain stores, including a Safeway at 44 Street and Sheriff Road in Deanwood, and lesser-financed Black-owned outlets that lacked the buying power of a cooperative or chain.

Today, one room food stores have given way to large full-service stores. Only three of these modern stores serve 150,000 people in Deanwood and other majority Black neighborhoods along DC’s eastern border with Maryland.

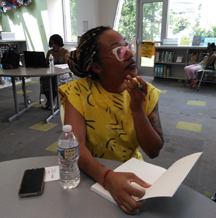

During her hour long talk at the modern Deanwood Library, Reese says that supermarkets don’t use race in their location decisions but use “racial indicators” such as college education and class. She surmised that the racially-colored location outcomes are the result of grocery stores “using race measures without using race measures.”

In the book, Reese, an assistant professor of anthropology at Spelman College, writes "In Washington, DC, as in many other cities in the United States, the chance of a full-service grocery store being nearby depends upon where a person lives. And, as research has shown, where a person lives is highly dependent on race and class.”

To arrive at her conclusions, in famed anthropologist Zora Neal Hurston fashion, Reese interviewed non-celebrity Black folks in Deanwood about everyday life, and in particular, their search for food. Instead of relying on catch-all terms such as White supremacy to explain the existence of the inequalities in food accessibility, she meticulously uncovers its tentacles - - and names them -- such as the 1968 riots and the advent of well-financed, full-service grocery stores that do not include “food justice” in their location equations.

Interestingly, one of the post riot-Black economic development outcomes resulted in transnational Giant and Safeway grocery stores mentoring Black owned grocery stores such as Baltimore, Maryland-based Super Pride. Super Pride operated a store at 51 Street and Nannie Helen Burroughs in a former Safeway store.

Another unexpected side dish of Reese’s spread is the exploration of Black consumer behavior. That behavior, at times, can seem as irrational as that of any consumer’s behavior such as when one group of Blacks expressed pride in a Black owned grocery store, but did not shop there.

While much of the book reads academically, it’s filled with many first person accounts of Deanwood residents’ food choice decisions. Many of the words used to describe their experiences are depressing, but funny such as calling the Safeway, “unSafeway,” or describing the community as a land of “nothingness,” as the interviewees describes the retail landscape as one of liquor stores and gas stations.

Supermarkets don’t use race in their location decisions today but use “racial indicators” such as college education and class. She surmised that the racially-colored location outcomes are the result of grocery stores “using race measures without using race measures.”

When responding to a question about the policy implications scattered throughout the book, she vehemently urged her audience of more than 50 people to read the national farm bills and to read and comment on the local East End Grocery and Retail Incentive Program Tax Abatement Act of 2017.

The local bill would establish major benefits and tax breaks for anchor stores, grocery stores, and sit-down restaurants that open in specific sites in Wards 7 and 8 (eastern wards along the Maryland border). Reese reminded the audience that restaurants and food stores are gentrification generators before declaring that the bill does not go far enough. She suggested that a better bill would include provisions to support food-coops and not relay heavily on big box stores to render food justice to the community.

Relying on corporations to straighten out structural food inequities is something that harkened Mawya Ceesay’s thoughts. In his native country, The Gambia, he says there are some western style food stores in tourist areas, where Europeans tend to also settle. “However, Gambians are not much affected by where better financed stores chose to locate since even urban Gambians prefer to shop at traditional markets and in traditional ways,” says Ceesay, who owns Newstyles Beauty Supply in Silver Spring, Maryland.

Only 15 minutes from Deanwood, in Greenbelt, Maryland, the Greenbelt Co-op Supermarket and Pharmacy has survived market and demographic transformations and in an aging shopping center. Like Gambians, Greenbelters survive by not relying upon corporations to deliver food justice.

As a coop, members own the store that currently brings in about $12 million a year in sales and about 8 of its 10 customers are members. As the store’s owners, the members share in the store’s decision making. “Therefore, we are more responsive to our community – that gives us a distinct advantage,” says general manager Bob Davis. Members also share in the profits and in the past 35 years, they have shared more than $2 million in profits.

Davis admits that if the store was a transnational, “it would be a struggle” to keep the store open. He added, “However, the people who are shopping here are the owners and a have a vested interest in keeping the store in the community.”