“Why do you listen to that old Spanish music?” That was the question my fellow African-American high school classmates would ask me upon discovering my interest in mambo. While the past 20 years have brought increased awareness, many African-Americans still allow Spanish-language lyrics to obscure the fact that salsa, mambo, plena cha cha cha, and other Caribbean genres flow from the same African root as jazz, blues, gospel, hip-hop and other Africa-American musical styles.

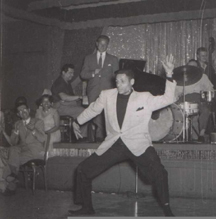

Not long ago, in the 1950s, a generation of Washingtonians and other African-Americans made a ritual of dancing at mambo clubs like the Casbah on U Street. Dancers such as Roland Kave performed for years on TV shows such as WTTG’s “Capitol Caravan” in the nation’s capital. New Yorkers went freely back and forth between the Palladium Ballroom and the neighboring jazz club, Birdland.

At the height of mambo’s popularity, in the early 1950s, Black magazines such as “Ebony,” “Sepia,” “Jet,” and “Hue,” routinely ran articles on mambo stars like Joe Loco, Tito Puente, and Perez Prado, alongside features on Dinah Washington, Sammy Davis, Jr., and Little Richard. Even if they didn’t speak Spanish, African-Americans recognized the rhythm as part of them and didn’t allow artificialsocio-political barriers to limit their musical choices and cultural awareness.

The form of mambo that became an international sensation between 1948 and 1958 grew largely from Afro-Cuban jazz, a genre created by Afro-Cuban trumpeter Mario Bauza, who was a classically trained clarinettist with the Havana Philharmonic before a Cuban ban tapped him for a brief engagement in Harlem in 1929.

Bauza was astounded at the thriving Harlem Renaissance scene. He also was fascinated with the music of his African-American brothers: jazz. In the following year, at age 19, Bauza emigrated to the U.S, to master African-American jazz.

By the mid-1930s, the gifted musician was regularly performing as a member of the legendary bands of Fletcher Henderson, Don Redman, and Cab Calloway. He held the first trumpet’s chair for several years with the Chick Webb orchestra, where he cemented a friendship with his then-roommate, trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie. Gillespie helped Bauza master jazz theory, while Bauza gave Gillespie his passsion for Afro-Cuban rhythms that would manifest itself in the following decade through the bebop movement.

By 1940, Bauza was ready to implement his revolutionary plan: to combine African-American big band jazz harmonies with authentic Afro-Cuban dance rhythms. He became musical director for the legendary band called Machito and his Afro-Cubans, fronted by his brother-in-law, the great singer Frank “Machito” Grillo.

The popularity of Afro-Cuban jazz among African-Americans was considerable, particularly in northern cities. In a 1992 article for “Interview”magazine, Eartha Kitt revealed, “I was an expert (mambo) dancer, a street dance. People like Machito and all those Cuban bands used to come to the neighborhood (Harlem) to play, and I was always the best girl dancer!” With no formal training, her skills as a mambo dancer enabled Kitt to face her audition for the renowned Katherine Dunham dance company, the job that launched her show business career in 1949.

Congas, maracas, and other traditional African instruments, which had been virtually absent from African-American popular music, were reintroduced during the 1960’s largely because of the popularity of mambo in the Black community.

African-American R&B groups often experimented with mambo themes. You can hear the impact of the genre on African-American music in the work of Bo Diddley, La Verne Baker, and others. The doo-wop group, The Harptones, even recorded “Mambo Boogie,” backed by Machito’s Latin rhythm section.

Listen again to Marvin Gaye’s “Baby Don’t You Do It” and “Stubborn Kind of Fellow” and Mary Wells’ “The One Who Really Love’s You.” Basic Afro-Latin patterns run through much of the classic Motown repertoire. Congas, maracas, and other traditional African instruments, which had been virtually absent from African-American popular music, were reintroduced during the 1960’s largely because of the popularity of mambo in the Black community. Today, you would be hard pressed to find an R&B band that doesn’t use African percussion instruments.

Whether we groove to hip-hop or Latin rhythms, the music we listen to is based largely on where the ship that carried our ancestors landed in the New World. In getting to know ourselves and each other, it is important to recognize the African heart that links all of the varied musical styles and populations of the Diaspora.