CR Gibbs

" A Negro boy has been executed at Vicksburg, Mississippi for assaulting his master."

- Daily Exchange, Baltimore, MD, March 7, 1860

From the time of slavery, Black children have been the objects of fear, suspicion, and malice by White society. Denied the right to play, gain an education, or even defend themselves from the horrors of slavery, they have come to represent an early phase of the ultimate existential threat to White supremacy.

African American children became that which must be surveilled, contained, and even eliminated before they could grow into what America considered an even more dangerous adulthood. Whatever internal notions they possessed of freedom, equality, justice, or humanity were criminalized whenever they were acted upon.

"A slave girl of sixteen attempted to run away from the plantation a year since, and was caught. General (Robert E.) Lee ordered her to be stripped to the waist and this was done in the presence of her mother. After the whipping the girl was taken to Richmond and there forwarded to some cotton plantation."

- Cincinnati (OH) Daily Press, June 15, 1861

To be sure, there are fair, honest police, prosecutors, and judges, but the problems Black youth and America itself faces are significantly institutional and multigenerational and can only be overcome by sustained assault from both outside and inside.

The end of two centuries of slavery brought no respite to the minds and bodies of Black children nor change to an injustice system where, inversely to the rest of America, Black children were and still are adjudged guilty until proven innocent. Some historians have called this period, from the end of Reconstruction until well into the 20th century, the "nadir of American race relations." Lynchings, beatings, Jim Crow, rapes, poll taxes, literacy tests, rigged trials, and peonage were the hallmarks of that age for people of African descent in America. In this maelstrom of little law and near total disorder, Black youth were targets of convenience.

The Scottsboro Boys 1931 - Alabama:

Nine young Black men between the ages of 13 and 19 were accused of raping two young White girls and fighting with a group of White boys while they were catching an illegal ride on a freight train. All the Black boys, except the youngest, were quickly convicted of rape and sentenced to death. They had committed the ultimate crime.

Nine young Black men between the ages of 13 and 19 were accused of raping two young White girls and fighting with a group of White boys while they were catching an illegal ride on a freight train. All the Black boys, except the youngest, were quickly convicted of rape and sentenced to death. They had committed the ultimate crime. As news of the trials began to spread outside of the South, several civil rights groups, including the International Labor Defense, associated with the American Communist Party, fought for an appeal. The appeal cited among other things ineffective counsel, an all-White biased jury, and the recanting of the rape charge by one of the alleged victims.

The boys were again found guilty. More trials followed, but Alabama injustice was unyielding. The convictions were finally overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court four years later. Nevertheless, the boys remained in jail. Later in a compromise deal, half of the boys went free with the others being sentenced to death or long prison terms. Some of the defendants tried to escape the excessively brutal conditions of the Alabama prison system because they had become marked men. One was killed in prison. Another jumped a hard won parole and fled north. Twenty five years after the last of the Scottsboro Boys had died, the Alabama parole board voted to give them posthumous pardons.

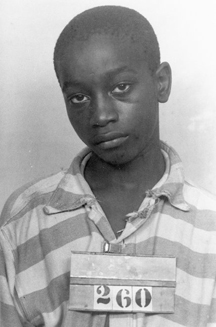

George Stinney 1944 - South Carolina:

At the age of 14, George Stinney became the youngest person executed in the United States in the 20th century. Charged with the first degree murder of two little White girls, Stinney was killed in the electric chair despite the lack of any physical evidence. His only link to the crime still appears to be that he spoke to the girls on the day of their deaths. Three local policemen claimed the boy had confessed, but they took no notes and were never questioned by his defense counsel who was actually a local tax commissioner stumping for an election. There is also no transcript of the trial.

At the age of 14, George Stinney became the youngest person executed in the United States in the 20th century. Charged with the first degree murder of two little White girls, Stinney was killed in the electric chair despite the lack of any physical evidence. His only link to the crime still appears to be that he spoke to the girls on the day of their deaths. Three local policemen claimed the boy had confessed, but they took no notes and were never questioned by his defense counsel who was actually a local tax commissioner stumping for an election. There is also no transcript of the trial. During Stinney's two and a half months of incarceration, his father lost his job and the family received death threats and was forced to leave town. An all-White jury was put together in a day. They reached a verdict in 10 minutes. Stinney was too small for the electric chair. They put books under him to get a better fit. He was only five feet, one inch tall and just a bit over 90 pounds. He died in less than five minutes. Recent research suggests a local White man may have been the perpetrator. Stinney's conviction was vacated in 2014.

More:

In more recent times, there have been a parade of flagrant miscarriages of justice: Emmett Till, seven of the famed Wilmington 10 were teenagers, three were also the Central Park Five, the Jena Six, and so many more Black children unfurl enmeshed in the hostile net of American jurisprudence. To be sure, there are fair, honest police, prosecutors, and judges, but the problems Black youth and America itself faces are significantly institutional and multigenerational and can only be overcome by sustained assault from both outside and inside.

Moreover, there must be a plan for after the protests. President Obama's observation that that racism is "deeply rooted" and "isn't going to be solved overnight" in our society are truisms that must be firmly faced by all of us before reform and healing can take place. A 2012 Associated Press poll revealed that 51 percent of Americans had "explicit anti-Black attitudes"-up from 48 percent four years earlier.

As the voice of the future, our youth must and should be in the vanguard of calling for just change and it is critical that we listen to their protests. None of us should stand idly by in this era of Ferguson, Staten Island, or the killing of little Tamir Rice in Cleveland.

As the voice of the future, our youth must and should be in the vanguard of calling for just change and it is critical that we listen to their protests. None of us should stand idly by in this era of Ferguson, Staten Island, or the killing of little Tamir Rice in Cleveland.History reminds us that there are periods of great protests when an inter nation chorus of voices swells around the globe advocating for positive change: 1968 when radicals contested with police at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, young people took to the streets of Paris and Czechs stood shoulder to shoulder to wret their Velvet Revolution from the talons of communism. Scarcely recalled today is 1989 when the Berlin Wall toppled, Russian communism expired, and young people hungry for change faced the troops and tanks of the Chinese military, or 2011, the year that hundreds of youths, Black and White, were arrested in the United States and around the world as part of the Occupy Wall Street movement. This was also the year of the luminous beginnings of the Arab Spring.

Perhaps destiny has summoned a new generation of Americans to fight the ongoing demonization of African American youth. Franz Fanon, the great Martinique-born psychiatrist, philosopher, author, and radical, noted many years ago that each generation must fulfill its mission or betray it. Perhaps the direction of the current generation of Black protest is the ultimate question of the hour.